Permission to Grieve: 'Human Acts' by Han Kang Book Review

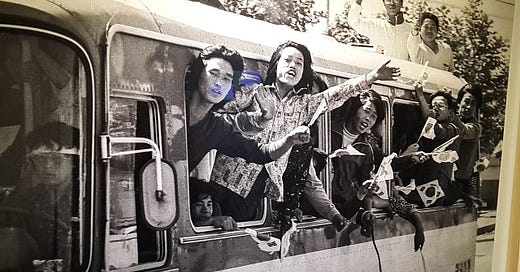

Remembering South Korea’s Blood-Smeared Road to Democracy

How do we process loss that is borne of injustice?

When the names of the fallen are buried in unmarked dirt, bound to become as unrecognisable as their mutilated bodies, is closure and acceptance still an option for the loved ones they died for?

And what of the ones who are responsible? Are those who pulled the trigger fundamentally evil? Or are we all liable to committing violent acts if merely endorsed to do so by authorities?1

Han Kang’s captivating story mapping the unreconciled grief of a nation encourages us to ponder about such insoluble questions, including one which has racked the brains of philosophers and muggles alike for generations – what is true humanity?

“I want to see their faces, to hover above their sleeping eyelids like a guttering flame… Until they hear my voice asking, demanding, why.”

Published in 2014, Human Acts follows the aftermath of the 1980 Gwangju Massacre – a democratic uprising calling for an end to South Korean military dictatorship and martial law. The ten days of demonstrations, spearheaded by students and joined by thousands of others from the local community, resulted in violent suppression by government forces, including indiscriminate killings, mass arrests, and detainee torture.

The novel commences with images of bodies, a number of whom have been marred to a point that the mere sight of them is described as “cruel”. They are lined up in an auditorium, shrouded in cloth, and awaiting identification. Middle-schooler and protagonist, Dong-Ho (revealed in the epilogue to be based off a boy involved in the uprising) is assisting in the care of his fallen peers, alongside two others. In the meantime, he is looking for a body among the dead – that of his missing friend, Jeong-Dae.

Han Kang’s entrancing second-person narration takes you through every step in Dong-Ho’s thoughts, actions, and surroundings.

From there, Kang guides readers through shifting character perspectives, dissecting the ways in which the tragedy of the massacre, which claimed at least 1,000 lives, maimed each of them over a 30-year period.

A Gwangju native herself, Han Kang’s prose draws attention to the ways politics are embedded into our personal, everyday lives. By seamlessly exploring struggles with PTSD, grapples with grief in an era of censorship, and authorities’ disregard for human life, this novel bursts with political dialogue without ever losing sight of the inner-turmoil and life-altering journeys of the people affected.

“The thin line of his lips, the stoop of his shoulders, the flecks of white in his hair. It's the soldiers, not him, that your death should have weighed on, so why did he grow so old before his time, so much quicker than all his friends? Is he still troubled by thoughts of revenge? Whenever I think this, my heart sinks.”

Mourning in Silence

Almost immediately after the slaughter took place in May of 1980, President Chun Doo-Hwan (who passed away in 2021 without ever taking responsibility for the crime) enacted the 1948 National Security Law to seize control over several media outlets, including dismissing 937 members of the press. Whilst the National Security Law was initially aimed at combating government infiltration, particularly from North Korea, it has been repeatedly scrutinised for suppressing and criminalising domestic dissidents and government opposition.

Though not explicitly mentioned, the abuse of this law seems to be at the root of much of the people’s troubles. The emotional weight of state neglect echoes through this story, as the characters struggle to accept not only the murders of their friends and families but the indifference of the leaders who callously overlook the crimes committed under their command.

By centralising Gwangju’s grievances in tandem with government cover-ups, Kang emphasises how state-sponsored censorship hampers a community’s ability to mourn. Indeed, how can we be expected to find closure in something we are unable to talk about?

Han Kang’s choice of the publishing industry as backdrop to this issue is an ingenious way to explore such policies, forcing you to realise even briefly, that the book you are holding would not have made it out of the editor’s room if it had been written just 30 years earlier.

“The censors had scored through four lines in the paragraph which followed that one. Bearing that in mind, the question which remains to us is this: what is humanity? What do we have to do to keep humanity as one thing and not another?”

Fight Together, Die Together, Grieve Together

Via the flashbacks scattered throughout the story, we learn that the paratroopers opened fire whilst protestors were singing the national anthem. In this brutal betrayal of confidence by country-runners and soldiers alike, the young Dong-Ho questions how the memorial services could still be adorned with national emblems; “Why would you sing the national anthem for people who’d been killed by soldiers? Why cover the coffin with the Taeguki [the South Korean flag]? As though it wasn’t the nation itself that had murdered them”.

But what constitutes the ‘nation’?

A loaded question for anyone to answer, let alone for a middle-school boy. However, it is clear to the people of Gwangju, that whilst the leadership was hellbent on treating the activists as “rioters” and a national security threat, the only traitors to the nation had been the leadership themselves.

The sense of community pulsates in this story. The students and workers who stood arm in arm against martial law, who chanted, “We are fighters for justice, we are, we are // We live together and die together, we do, we do // We would rather die on our feet than live on our knees”, are cared for after death by each other’s loved ones and peers. Their stories are preserved, investigated, retold in secret, and forced through the censors in whichever way they can. And so, in a perilous void and in the face of treachery, the resistance goes on. It is the people, not the state, who ultimately define how this event will be weaved into the fabrics of their nation.

A Universal Story of Violence and Grief

It is at once shockingly and tragically easy to substitute a handful of details of the Gwangju Uprising, and picture another similar moment; at another location, in another point in time, the story of Gwangju, South Korea will be familiar to many of us.

While wading through the characters’ bloody testimonies and childhood traumas, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to the Tiananmen Massacre in China, the 1961 Paris Massacre, the Palestinian Great March of Return. The endless horizon of suppressed resistance movements that devastated human life and in which authorities and the media went to great lengths to cloud and/or justify the calamities in the aftermath. How common it is that we are slaughtered and silenced for demanding we be treated as human.

Kang encourages us to make these connections, questioning if the globality of such events is proof they are an inevitable fact of humankind. The Vietnam War is referenced more than once, not simply for its terror against the Vietnamese (in which South Korea’s own military played a part in), but to highlight how the conflict dehumanised soldiers, turning them into machines incapable of seeing the person on the other side of the gun as another human being.4

It is implied that, as people, this is simply what we do. That under the right circumstances, we are all capable of committing such heinous acts, just as much as any of us could one day become the victim of such acts. Much like Kang says, “with such uniform brutality, it is as though it is imprinted in our genetic code”.

Final Thoughts

I don’t necessarily believe the goal of Human Acts was to leave us with these bitter realisations. In the case of Gwangju at least, there appears to still be hope for healing. Government reform over the last few decades has loosened state censorship, making space for memorialisation. In addition, there have been intergenerational confessions through the grandson of Chun Doo-Hwan, who visited Gwangju this year to acknowledge the crimes of his late grandfather and offer apologies to the victims’ families. Given that the Gwangju Uprising was the beginning of the end of South Korean military rule, maybe the takeaway is also that our circumstances have to get worse before they get better, and to remember those who have sacrificed the irreplaceable for us to stand here today.

To conclude, Human Acts splendidly captures the various motions of resistance and preserves the memories of activist youths who championed South Korea towards democracy. Though at times, the shifting viewpoints make it not immediately clear which character is being centred, this minor drawback can easily be forgotten through the novel’s thought-provoking portrayal of a beaten down people refusing to let their maltreatment be forgotten.

Partly because of Kang’s alluring prose, and partly because much of the story hit close to home, this was a gut-wrenching read. And yet, as my damp eyes followed closely across the final lines, there was something in me that didn’t want it to be over. I clung on to this novel’s every word.

For marvellously expressing the heartbreak of a national tragedy, memorialising the forgotten, and offering a voice to the ungrieved dead, Human Acts gets 5/5 stars.

It gives weight and meaning to bodies unaccounted for and to the bereaved families who fought for their recognition. Their search for closure in an era of continuing censorship and betrayal is a battle through which Han Kang confirms that the personal is indeed political.

To whoever picks up this book, I am confident that the memory of the martyrs will be able to live on.

“so even after I lost you, it had to go on. I had to make myself eat, make myself work, forcing each day down like a mouthful of cold rice, even if it stuck in my throat.”

Further Reading/Research

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt presents this idea in her essay Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963) where she argues that evil acts are often motivated by a responsibility to obey orders rather than an innate hatred and amorality in the evil-doer.