Rethinking the Politics of Solidarity with Audre Lorde

Book Review of ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House'

In a social environment of increasing individualism, I fear that we are losing the art of considering how we can better support each other. What does it truly mean to stand in solidarity with someone? How do we position ourselves and process our emotions in a way that is productive to social good?

Picking up dust on my TBR for several years, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House is a collection of five short essays by Audre Lorde which put into question our shortcomings in the fight against oppression. And though there is a part of me that wishes I had read this book sooner, the fact is, it came into my life at the perfect time.

“And when I speak of change, I do not mean a simple switch of positions or a temporary lessening of tensions, nor the ability to smile or feel good. I am speaking of a basic and radical alteration in those assumptions underlining our lives.” (Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism)

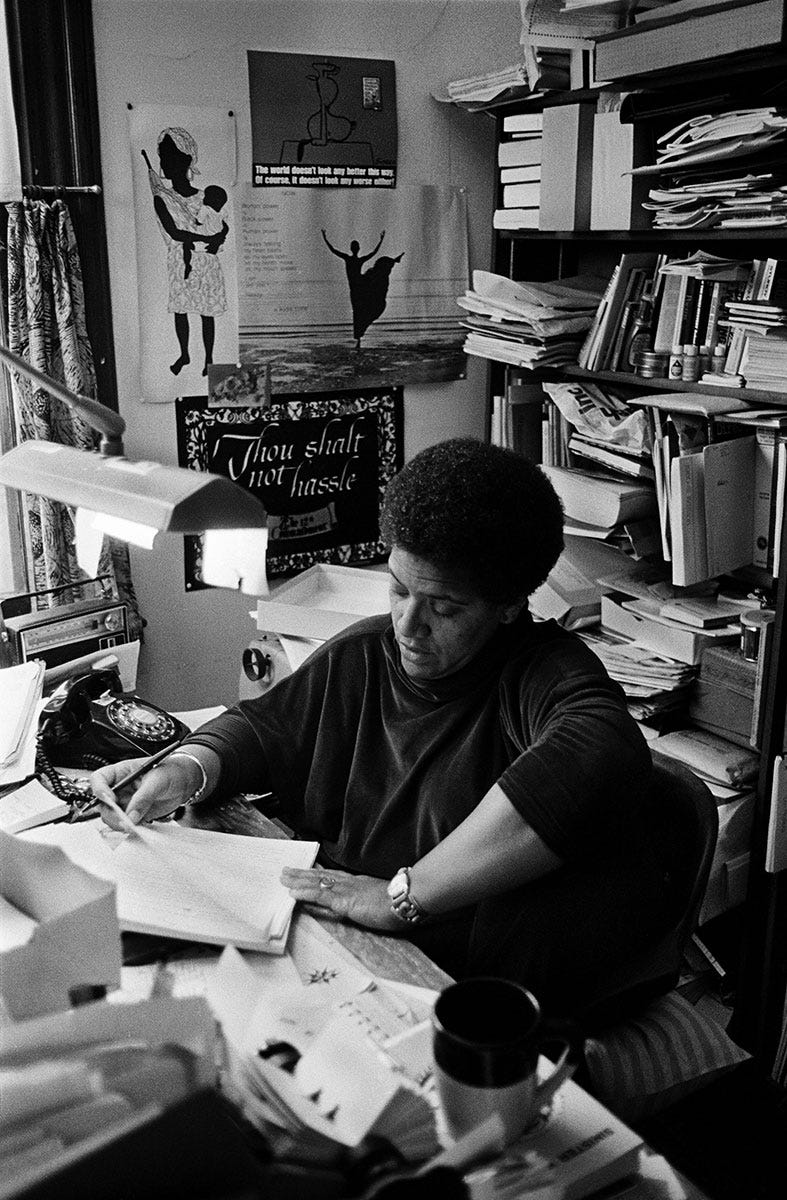

Audre Lorde (1934-1992) was a writer and activist born to Caribbean parents in New York City. Self-described as ‘Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet’, her writings focused predominantly on these varying aspects of her identity, and later on explored her struggles with breast cancer1. In 1991, she became the New York State Poet Laureate, a position she held until her death the following year.

As a prominent figure in 20th century Black, women’s, and LGBTQ+ movements, it is fitting that her five essays: Poetry Is Not a Luxury; Uses of the Erotic; The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House; Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism; and Learning from the 1960s (all published between 1977-1982) debate topics ranging from white feminism, our relationship to art, community, and the role of anger in resistance.

Though hardly one to look at the world through rose-coloured glasses, I believed that we had at least moved past myopia; that when the crimes were staring at us so flagrantly through our social media feeds, we at the very least wouldn’t deny them. My belief system soon dismantled, I turned to this book in response to disillusionment and in search for motivation.

Unlearning

“For as we begin to recognize our deepest feelings, we begin to give up being satisfied with suffering and self-negation… Our acts against oppression become integral with self, motivated and empowered from within.” (Uses of the Erotic).

This text is decolonial, challenging the relationships we build with our work, our art, with each other, and with ourselves.

Lorde argues that these relations, which are frequently defined by structures of “profit, linear power, [and] institutional dehumanization” ultimately leave us feeling disconnected, for within these structures, “our feelings were not meant to survive” (Poetry Is Not a Luxury).

Encouraging us to look inwards, she calls for what I would dub an ‘internal decolonisation’. Through this process, we can re-centre our feelings, and reevaluate our relationships to ourselves and those around us to allow greater space for integrity, balance, and innovation.

No meaningful change can be borne out of complacency to the status quo. As Lorde argues, if the tools of oppression are used to “examine the fruits” of that oppression, “only the most narrow perimeters of change are possible”. Dismantling these failing frameworks is thus amongst the most crucial steps towards liberation. “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” (The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House).

“Can we really still afford to be fighting each other?”

(Learning from the 1960s)

It is not enough to say that you support a cause. How do our stances translate into meaningful action? Do we look at ourselves honestly enough to digest criticism? Can we notice the gaps between our words and our behaviour? Are we then determined enough to turn what we say into consistent values and principles?

In The Master’s Tools and Uses of Anger, Lorde draws attention to the exclusion of Black women from mainstream feminist spaces. She denounces those self-proclaimed feminists who are far more focused on preserving themselves than in acknowledging their limitations - that is, in failing to accommodate for the experiences and testimonies of “poor women, Black and Third World women, and lesbians”.

Advocating for intersectionality, Lorde underlines the responsibility we each have to listen sincerely to one another; “If I participate, knowingly or otherwise, in my sister’s oppression and she calls me on it, to answer her anger with my own only blankets the substance of our exchange with reaction.” (Uses of Anger).

Lorde calls for two main realisations: firstly, we must recognise that “Without community there is no liberation”.

She stresses that painting our differences in a negative light only distracts us from working towards our shared goals. Naturally, unbreakable solidarity cannot be built if the people are at odds with each other. This only strengthens the divide and rule tactics of those one is struggling against3 . “And we must ask ourselves: Who profits from all this?” who benefits from our division? The movement is surely what will suffer most.

What we owe to each other

This does not mean that anger has no place in liberationist movements. On the contrary, anger’s “object is change”4.

“Anger is an appropriate reaction to racist attitudes, as is fury when the actions arising from those attitudes do not change.” (Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism)

Lorde urges us to repurpose our anger. Rather than turning against one another, we must recognise that our negative emotions can be channelled into positive outcomes. Anger is not irreparably destructive, but a tool for growth. “Focused with precision [anger] can become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change.” By extension, our feelings of helplessness do not have to be met with immobility but can in fact motivate and overwhelm us into action.

For drawing attention to the acts of resistance that must happen internally, and reminding me of what is truly important to evoke change, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House gets 5/5 stars.

Evidenced by my copy being littered with annotations and scribblings, I left this book with a lot to think about. But as I flicked through the pages again for this review, I realised I have few ways of sharing Lorde’s ideas as well as she. Every word put to the page is of value, handpicked with intent, precision, and care and serves as a starting point for building a future with community at the centre.

Notes, Further Reading/Research

The Cancer Journals (1980) documents Lorde’s own experience with breast cancer which she was diagnosed with in 1977.

Portrait of Audre Lorde working at her desk (1981) around the time that she was writing her autobiographical novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982). Image available here.

In his magnum opus Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), Brazilian revolutionary and educational theorist Paulo Freire argues that “sooner or later the oppressed will… discover that as long as they are divided they will always be easy prey for manipulation and domination… [they] must dedicate themselves to an untiring effort for unity… in order to achieve liberation”.

Emphasis added.