For the growing subculture of readers on TikTok who have decided to make this book their entire ‘aesthetic-sad-girl’ personality, I will not be joining you. But I’m beginning to understand the timelessness of Sylvia Plath.

This book also has an iconic opening line.

“It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.”

Depression was a highly taboo topic in 1950s-60s America. Whilst neuroscience was making fast progress, namely with the founding of antidepressants in the early 1950s, mental illness was still a growing field of study, (and is expanding ever still). So, when American poet Sylvia Plath published her first and only novel The Bell Jar in 1963, much of the troubles she expressed fell on deaf ears.

The Bell Jar is a semi-autobiographical account of Plath’s experiences whilst interning for a New York City magazine in the summer of 1953. Initially published under a pseudonym, the novel explores the growing cynicism of 19-year-old aspiring writer Esther Greenwood as she grapples with self-confidence and identity, whilst being overwhelmed by various desires and expectations.

Similarly to Plath’s own life, Esther’s downward spiral is triggered by a literary rejection and deep feelings of inadequacy. The pain of this rejection is severe to a point that Esther falls into a depressive period and is hospitalised for treatment.

“I had been inadequate all along… The one thing I was good at was winning scholarships and prizes, and that era was coming to an end.”1

Otherwise known for her seminal realist poetry, introspective journals, and abusive marriage to the English poet Ted Hughes, Plath remains a controversial figure across literary and pop culture. In parallel to the novel’s protagonist, she was diagnosed with clinical depression at 20 years-old and subjected to electroshock therapy as part of her treatment. After numerous suicide attempts, she finally took her own life on the 11th of February 1963, aged 30, just a few weeks after The Bell Jar’s release.

Sixty years on, her untimely and unusual death-by-oven-gas has cemented her as a poster-child for depressed young women caught between the burdens of ambition and womanhood. But I’d rather not spend this review making a further spectacle of Plath’s turbulent personal life.

On the one hand…

I could have probably gone through life without this book.

I had often heard of Sylvia Plath in passing and gathered random details about her over the years. However, this was my first time delving into her works. With endless reviews and book-tok opinions floating around about how gut-wrenching and soul-churning the story was, I too was hoping to find a similar profundity.

But it seems my expectations were set a little too high.

Despite its deadpan humour and interesting subject matter, I can’t say I enjoyed this book. Whilst I’m not normally a reader who has to find a character relatable (or even likeable) to feel invested in them, I wasn’t moved by Plath’s narration. That is, I felt very disconnected and indifferent to it. The structure was more anecdotal than reflective, (which I found rather odd given its focus on mental health), and spent a great deal of time discussing other characters that I had no particular interest in.

I tried to explain this away as a portrayal of denial or confusion about her internal goings-on. But, as someone who favours character insight, this outward look at depression failed to create much empathy in me towards Esther, and by the end of the novel I only managed to feel routine human sympathy for her unfortunate circumstances.

Bell Jars, Fig Trees, and Gen-Z

Whilst I didn’t find The Bell Jar an engaging (let alone life-changing) read, it still left me with much to think about.

Perhaps due to a shrinking stigma on mental illness and higher rates of depression and anxiety in young people, the novel has seen a resurgence in popularity amongst Gen-Z, most notably through the infamous ‘fig tree’ metaphor:

“I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig-tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, … unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and… they plotted to the ground at my feet.”

Many teens and young adults have understood the fig tree as a symbol for our fears of going down the wrong path. Esther is fascinated by the endless possibilities of life – from becoming a writer, to studying German, to making pottery – but she knows that all of those personal ambitions in tandem with social pressures (particularly as a woman2) are impossible to simultaneously fulfil. The thought of being one thing, trapped “under the same glass bell jar”, suffocates her to the point of grief.

Along with the often overlooked titular metaphor, the visuals of figs wrinkling before they have a chance to be picked resonated with me deeply. As a member of Gen-Z, I know this feeling all too well; there is an immense helplessness in witnessing our dreams clash with the precarity of our futures. How the lack of assuredness that we’ll get even a handful of what we want makes us hesitant to pursue anything at all.

I believe that Plath, despite everything, was profoundly in love with life3. That it was this love, that was so often rejected or stifled, which overran her with fear, and that she mourned an unrealised future where she wouldn’t be able to experience all that had the potential to be loved.

For providing an enduring coming of age story in a slightly boring but nonetheless, thought-provoking manner, The Bell Jar gets 3/5 stars. Beyond a handful of extracts, this wasn’t a cathartic body of work for me, like it seems to be for so many others. Despite being underwhelming, it hasn’t put me off wanting to read her other works. I’m hoping that once I tackle those, Plath will simply prove to be more of a poet than a storyteller.

Further Reading/Research

Plath had a stellar academic record. She graduated from Smith College in 1955 with an English degree and then won a scholarship for postgraduate English studies at Cambridge University. She also won several prizes for her poetry, including a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1982.

Andrew Solomon states in his book The Noonday Demon that women “may become depressed as a consequence of being unable to live within a stultifying definition of femininity”.

Sylvia wrote in her diary: “I can never read all the books I want; I can never be all the people I want and live all the lives I want. I can never train myself in all the skills I want. And why do I want? I want to live and feel all the shades, tones, and variations of mental and physical experience possible in my life. And I am horribly limited.” Her diary was published posthumously in 1982 as The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath.

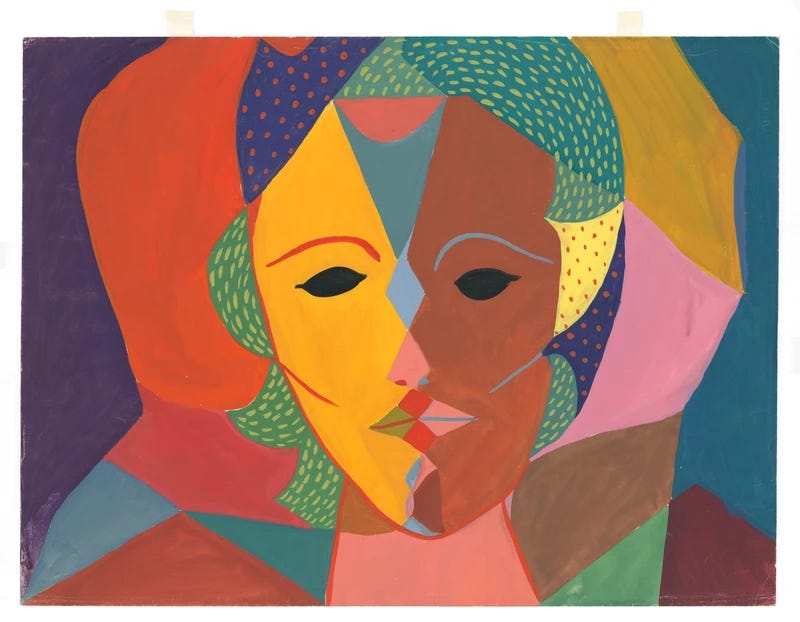

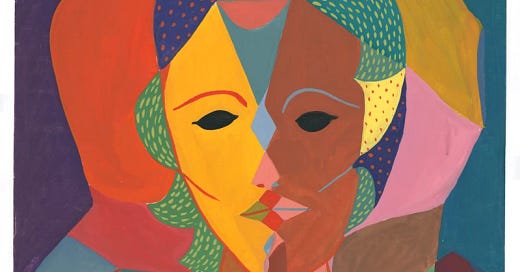

![Book cover reading "The [Sylvia] Bell [Plath] Jar" Book cover reading "The [Sylvia] Bell [Plath] Jar"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff5b2b906-75ac-4dbb-a3f6-51036a746470_652x1000.jpeg)